I could very well deliver a generic answer about Concurrency x Parallelism, but I don't think I'd like that very much. So... last weekend, I studied more about how processes used to work on our computer. So to start talking about concurrency, I think it's interesting to start with the topic of "subroutines a.k.a procedures"

Subroutines

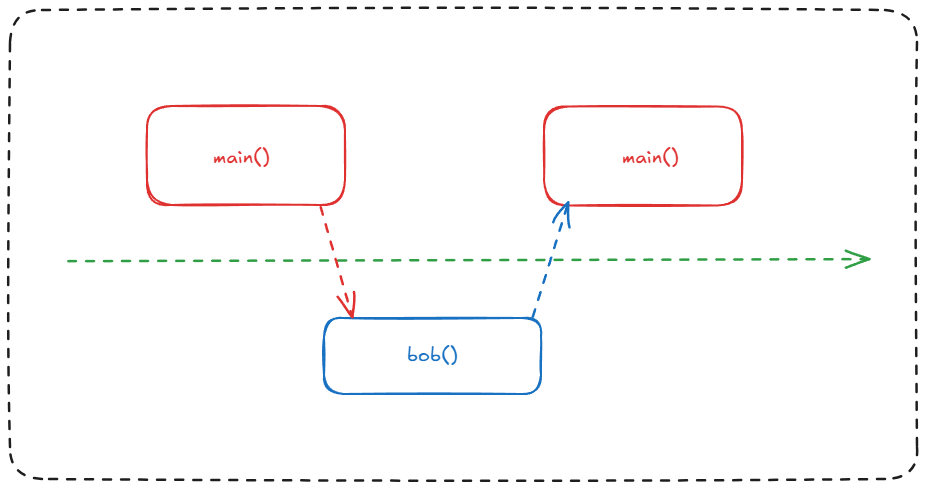

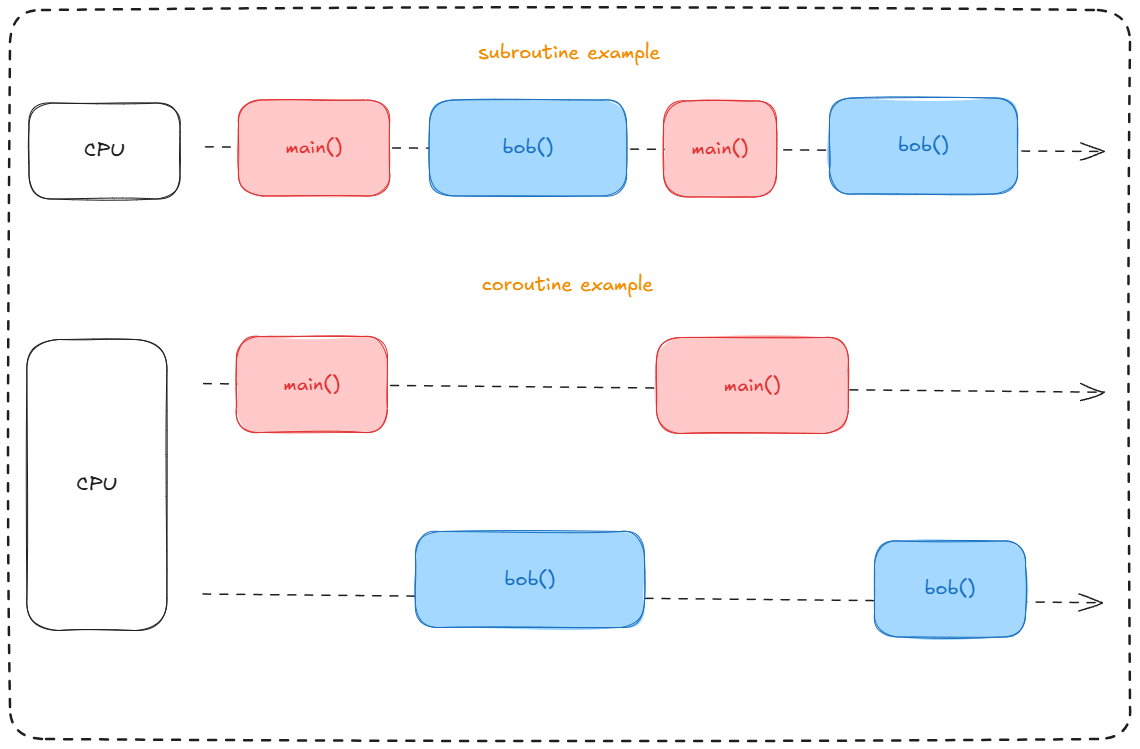

As you can see in the drawing below, a subroutine (also known as a procedure) is basically an executable unit that can be called in our main function. For example, let's say we have a main() function that executes a series of processes, and these processes are subroutines of our main() function. We have a bob() subroutine, and it is called inside the main() function. They will be executed sequentially; that is, main() will call bob() and then return to main(). In other words, main() will call bob(), bob() will be called, and then return to main(). But it's also worth remembering that once a subroutine has finished, it will return from the beginning again. If it is called again, it will start again from its initial step, which is very different from coroutines.

Coroutines

Coroutines have been around for a long time, and back in the day, processors weren’t multicore. If I’m not mistaken, the first "popular" multicore processor was launched in 2009—the Intel Core 2 Duo (there was also the IBM POWER4, but it was the Core 2 Duo that made this technology mainstream for consumers). Knowing this, let me ask you a question: how did our computers manage to run, "simultaneously," our OS, Tibia, and other processes? The answer is coroutines. These processes weren’t truly simultaneous, but their contexts were switched so quickly that they seemed to run in parallel.

Coroutines have a special ability, unlike subroutines, they can "pause", i.e yield. They pause, save their context, and then other processes can run, creating the illusion of parallelism. In reality, it’s just a rapid alternation of tasks, all controlled by our Scheduler. However, our OS didn’t always work this way. There are other methods for executing this "task list," but they are quite similar.

Here is a code example showing how subroutines and coroutines behave.

1function subroutine() {

2 return 1;

3 return 2; // dead code

4 return 3; // dead code

5}

6

7subroutine() // 1

8subroutine() // 1

9subroutine() // 1

10

11function coroutine() {

12 yield 1;

13 yield 2;

14 yield 3;

15}

16

17coroutine() // 1

18coroutine() // 2

19coroutine() // 3

Parallelism

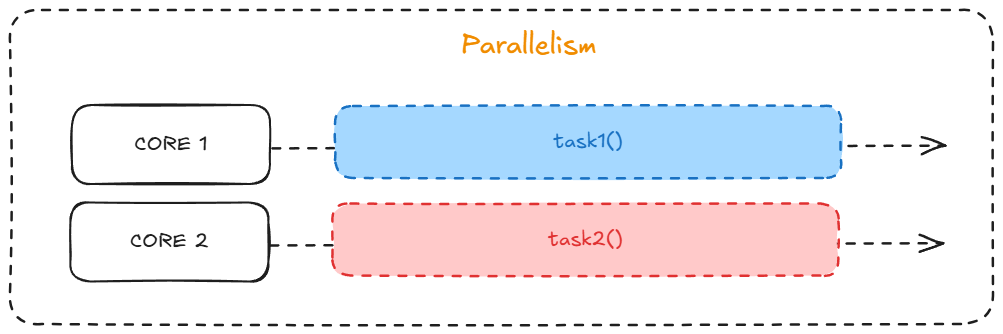

Well, the next step is a generic part about my studies. It's necessary to explain how parallelism works, with a short description. Let me say you have a process running in thread 1 and another process running in thread 2; they're running in parallel, right? Yes, because a thread is a sequence of logical flow, and we are running two flows at the same time. This works because of multicore processors. Parallelism is intrinsically linked to multicore capability.

After this explanation, we realize that parallelism can be faster than concurrency because context switching can become a significant cost, depending on how concurrent your application is. But, as always, it depends a lot on the implementation—parallelism being faster is not a universal rule.

Race Condition

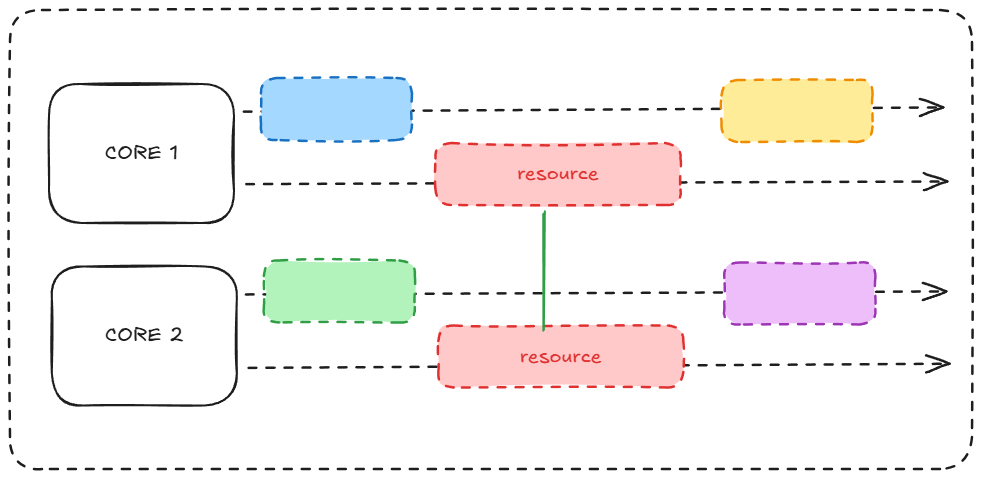

One way doesn’t exclude the other because it can work both ways at the same time. For example, in thread 1, our program runs several tasks at once, and the same happens in thread 2. Eventually, we run into a problem: process A can’t switch with process B in the task queue. But if the scheduler decides they should switch anyway, the program could end up in conflict, with both processes trying to access the same resource at the same time, leading to unexpected results.

A good example of this is a bank account: imagine you withdraw two amounts at the same time, but the system wasn’t prepared for this. Let’s say your account has R$ 2000, and you try to withdraw R$ 1700 and R$ 1500 at the same time. Since the system doesn’t handle simultaneous transactions properly, it sees both withdrawals as valid because they each check the account balance of R$ 2000. They’re not “ordered,” and this causes an issue.

In Go, we can control access to resources using Mutex and Channel. In my experience with Go, Mutex often solve concurrency problems because they allow us to "lock" a resource until one process has completely finished using it.

1package main

2

3import (

4 "fmt"

5 "sync"

6)

7

8type BankAccount struct {

9 balance int

10 mutex sync.Mutex

11}

12

13func (a *BankAccount) Deposit(amount int) {

14 a.mutex.Lock()

15 defer a.mutex.Unlock()

16

17 a.balance += amount

18}

19

20func (a *BankAccount) Withdraw(amount int) error {

21 a.mutex.Lock()

22 defer a.mutex.Unlock()

23

24 if a.balance < amount {

25 return fmt.Errorf("Insufficient balance")

26 }

27

28 a.balance -= amount

29 return nil

30}

For example, in the case of withdrawals, the R$ 1500 withdrawal would have to wait until the R$ 1700 withdrawal is finished because both are trying to access the same withdrawal functionality. The idea is that one process holds the lock while it's working with the resource, and the other process has to wait.

So, after the first withdrawal of R$ 1700, the remaining balance would be R$ 300, and the R$ 1500 withdrawal would no longer be valid. This kind of error is quite common, but because it's so typical, it's relatively easy to find solutions and fix it (though, of course, it depends on your codebase, but let’s assume that’s the case).